Troy Paiva, whose work is handsomely reproduced in Chronicle Book’s recent Night Vision, is one of the acknowledged masters within the small cadre of professional night photographers. The stunning photos in this monograph demonstrate the high quality of Troy’s work.

Troy Paiva, whose work is handsomely reproduced in Chronicle Book’s recent Night Vision, is one of the acknowledged masters within the small cadre of professional night photographers. The stunning photos in this monograph demonstrate the high quality of Troy’s work.

These are images of crumbling ruins in the American west ranging from abandoned military bases and resorts to the old train station in Oakland, airplane part junkyards, and erstwhile roadside attractions. If it is romantic, seedy, falling down, and visually arresting it is grist for Troy Paiva’s night time mill, who previously mined this vein in his classic Lost America: The Abandoned Roadside West.

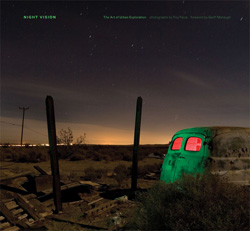

Night Vision is subtitled The Art of Urban Exploration, which strikes me as a bit odd. Certainly, the fascinating photos in this book and the related stories are about the archeology of recent human culture. But they are not particularly “urban.” In fact, with the exception of the wonderful series of photos of the old Oakland train station, this work shows isolated or even rural settings (you can get a sense of this even from the book’s cover).

While Troy Paiva’s writing is lucid and compelling, I also don’t have much use for the trendy and mostly irrelevant opening essay, Desert Iliad by Geoff Manaugh.

Troy writes that he shot film until fairly recently, switching to digital in 2005 (about the time I did). I believe that most of the photos in the book were taken with digital equipment. Troy’s preferred subject matter and technique differ from mine. He is looking for lost human artifacts at night, I primarily like the natural landscape. Troy’s exposures are in the 2-4 minute range, and he light paints with flashlights and gels. My exposures are often far longer, and I’m not that interested in colored light painting. These differences help point out the vast vocabulary range available in night photography, and why this is an exciting area for many people.

In his description of his technique, Troy writes that mostly he doesn’t post process his images much: “These captures are virtually untouched, straight out of the camera, with all the scene’s warts and blemishes intact.” Why Troy thinks this is a positive is unclear to me, although obviously many people share this viewpoint. (I won’t go into the argument in great length here, but a digital camera is a computer with a scanner and lens attached, so why not do some of the processing on a computer with greater capabilities?)

I highly recommend this book for three different reasons:

- You can learn techniques of night photography from a master.

- Troy’s stories of getting these photos on location in crumbling America are a great tale of adventure.

- The images are stunning, and worth the price of admission on their own.

Lost America

10 Aug 2008Thanks for the review. Let me clarify and comment on a couple of things.

It’s pretty well documented that the “urban” in urban exploration means the “man-made landscape” and not just cities. Some of the most famous UE locations like Bannermann’s island, dozens of Kirkbride asylums and countless military installations are located far from cities.

And while I have no problem with your photographic quality scan of a flower, saying the “digital camera is a lens attached to your computer” sends the wrong message for photography in general. Relying on digital means to create a good/usable image from inferior original work sends the whole nature of photography down a slippery slope. The thing that makes photography different from every other visual medium is that is is an actual chunk of time, recorded on the film or sensor. It has an immediacy, a reality that is totally unique.

It’s when someone turns a photograph into what is essentially a digital painting that they then pass off as a real photograph that they lose me. How would you feel about someone faking the crepscular shadow effect you captured on page 72 of your Golden Gate Bridge book in Photoshop? I don’t know about you, but I want that to be REAL when I’m looking at a photograph. Real in photography is a special moment captured, fake is . . . fake.

So by saying “your digital camera is nothing more than a lens on your computer” you open yourself up to having the very thing that makes photography special thrown away.

One more thing: I have to “leave all the warts and blemishes intact” because my photographs are basically OF piles of warts and blemishes! That original comment was not directed at covering any technical limitations in the gear or photographs.

And even if there were visible technical blemishes in the work, there are plenty of people that find imperfection in art to be intrinsic to the artistic process. What do you say to all the toy camera / Holga / Diana shooters out there?

texbrandt

11 Aug 2008In the end the camera is a tool for abstracting an image. No matter what you do or don’t do with what comes out of the camera whether it is on film or in digital format it is an abstraction. The analogy for me as a worker in wood, would be something like, well I just put this chair together with all the splinters and saw marks just as it came from the mill.

I keep coming back to the statement that the purpose of the artist is to make visible not merely to reproduce the visible.

It would make more sense to me to say by way of explanation for “the warts and blemishes” I enjoy seeing what the camera alone will do without making a virtue of using only a part of the available tools. To each his own.

One further word on tools. Some years ago I was sitting at an art show playing a Native American flute made by a friend of mine. A man walked up looked at the flute and commented in a derisive tone of voice, “looks like he uses power tools.” as if that somehow made it an inferior flute. (it was in fact a very good sounding flute) In reply I pulled out my pocket knife and laid it on the counter. “There,” I said, “is a power tool. It isn’t under power at the moment.” Then I picked it up and opened the blade and said, “now it’s under power.” Unless you elect to do everything with tooth and toenail, you will have to use a tool, and every tool by definition is a form of power tool. Tools do not make or not make art, somewhere there has to be an artist. A great artist will produce great art no matter what tools he uses. A lessor artist may be aided by better tools, but he will not be a great artist because of them. Your mileage may vary.

Robert

http://texbrandt.com

Harold Davis

11 Aug 2008There’s no real doubt that (at least from a technical standpoint) a digital camera is a computer attached to a scanner and lens. If you open the thing up, you’ll find at its heart an electronic circuit board. As Troy Paiva [“Lost in America”] wrote me in a side email, ‘for the record, I have no issue with agreeing that “The digital camera is a computer.” The rub for me is all in what people DO with it!’

So the question at issue between Troy and me speaks to the soul of photography. What should photography be? What makes a good photograph? What is the role of the photographer? How much manipulation is acceptable? Essentially, Troy’s complaint boils down to his statement that calling a camera a computer “sends the wrong message.”

Let’s look at the issues that Troy brings up a little more carefully. Here are some of the propositions in his comment and clarification with my responses.

Relying on digital means to create a good/usable image from inferior original work sends the whole nature of photography down a slippery slope. Of course, I never propose intentionally creating an inferior original work and then fixing it digitally. I’m a strong proponent in my book “Light & Exposure for Digital Photographers” and elsewhere of creating the best in-camera original possible, but I also keep in mind digital post-processing possibilities, and sometimes shoot to create the best captures I can with digital processing in mind at the time of capture.

I don’t know about you, but I want that to be REAL when I’m looking at a photograph. Real in photography is a special moment captured, fake is . . . fake. The question of what is real is itself, of course, a slippery slope, and one that can lead into all kinds of philosophic considerations. I’m hard put to see how lighting a night scene with flash lights and colored gels is any less “fake” than creating the same effect in Photoshop. The illusion of apparent reality is one of photography’s strengths as a medium, but anyone who accepts this illusion as reality is naïve. I think a better way to look at this is that a photograph is a representation that may be documentary in intent. Usually, you only have the photographer’s word on it: was that flag raising at Iwo Jima real or a recreation (er, fake)? So, no, I’m not looking for my photos to be a real special moment captured (I’m not even sure this is theoretically possible).

By the way, it is also possible to use post-processing to theoretically make a photo “more real” as in “I am trying to recreate the intensity of what I saw.” For the most part, I tend to eschew this line as a half measure meant to placate the dogmatic “photography is reality” school.

The thing that makes photography different from every other visual medium is that is an actual chunk of time, recorded on the film or sensor. This is a highly debatable statement. It brings up a number of questions along the lines of what does it mean to record “an actual chunk of time”? Can an “actual chunk” of time actually be recorded?

Rather than helping Troy refine his metaphysical rhetoric, I’ll speak to the proposition that I think he meant to make, that the portrayal of the passage of time is crucial to photography. I agree that many special photos get their power from the way elapsed time is captured, but it’s a big world, and there are many qualities that can make photos powerful. These include color, composition, narrative power (the ability to tell a story), emotional power (getting an emotional response from the viewer), clarity of rendering, and clarity of vision. Sometimes these components of the compelling image relate to time; sometimes they do not.

And even if there were visible technical blemishes in the work, there are plenty of people that find imperfection in art to be intrinsic to the artistic process. Me, I’m very catholic (with a small c) about the whole thing. If people want blemishes that’s fine with me, though I’d prefer the blemishes serve an artistic purpose.

Why, you can even have digital blemishes, such as noise or bad pixels. (In my chapter on noise in “Light & Exposure” I suggest that, despite the common goal of eliminating noise, at times digital noise can be beautiful.)

The summary here for me is, different strokes for different folks. I’ve made no secret that I manipulate almost all my images (see for example When is a Photograph Not a Photograph? ) For this reason, I try to refer to my work as imagery rather than the more specific photography. To me, the only thing that would be wrong would be to make false statements about the degree of manipulation in an image. (But this highlights the fact that in terms of capturing reality one is essentially buying the creator’s certificate of authenticity, which may not be worth the virtual paper it is printed on.)

Troy speaks dismissively about “turning a photograph into what is essentially a digital painting.” In contrast, I love thinking of my images as one part digital painting. I’m very happy for Troy to go on working his own way, but for myself I’ll take the put-down and revel in it.

When I say early in the digital landscape workshop that I give that I don’t care “what’s really there,” usually the students collectively gasp. But for the most part I don’t care about reality, which can be boring and mundane. I care about image making.

Digital has liberated photography from the real, if it ever was moored to it. It’s not unreasonable to treat reality as an illusion (or collective consensus) rather than something immutable and defined by the laws of the universe. Photography defined as digital image making can no longer hide behind the excuse of reality (“but that’s the way it was, it’s not my fault it came out so bright/dark/fuzzy/brown/whatever”). At the same time digital photography can now take its place on the stage of artistic mediums as a full-fledged citizen, capable of creating anything within the grasp of the technical skills, craft, and vision of the artist.